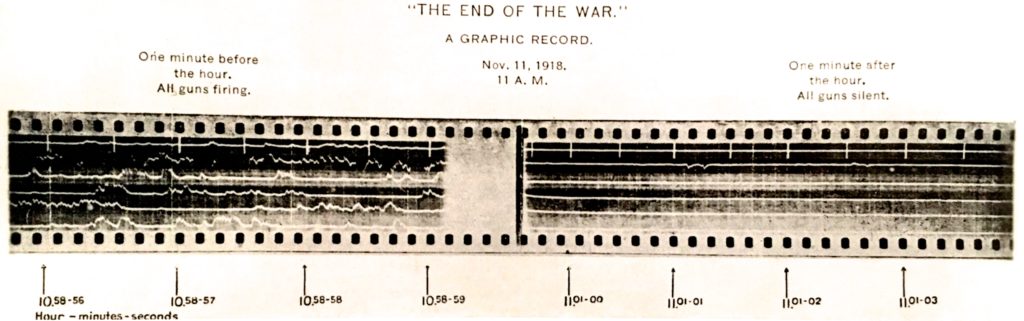

On 11 November 1918, at eleven o’clock in the morning, the last shots on the Western Front were fired.

For all, relief at the war’s end. For the Allies jubilation; for Germany despair and demoralisation. Especially for Germany’s Navy. Although undefeated in battle, it was a fleet in the throes of mutiny and dissent brought on by poor conditions for the men and the Fleet Command’s plan to use the Fleet’s still capable threat, for a last battle, days from the war’s end. Conditions aboard the Kaiser’s ships had been so bad that already in the summer of 1917 there had been open unrest.

In a train carriage at Compiègne, Germany’s political and military representatives were forced into accepting terms for a ceasefire. On another train, the ex-Kaiser and his family went into exile. 52 other wagons were attached – with all the Hohenzollern treasures that he could take with him.

Key to armistice process was the decision to intern the High Seas Fleet as a guarantor of Germany’s good faith while the peace negotiations were carried out in Paris, at Versailles, in the Hall of Mirrors where, almost a half century before, the new German Reich had been proclaimed.