The whaler Ramna after running aground on

Moltke. (Courtesy Kirkwall Library and Archives L202/1 941.09 B)

The scuttling of the German Fleet saved Orkney from the worst effects of the Great Depression. It created a new industry built up centered on salvage. There was a lot of it. Around 417,000 tons.

It soon became clear that the ships needed to be salvaged, moved or destroyed. Local ships would run aground on the shallower vessels. Fishing nets would foul on the deeper lying ones.

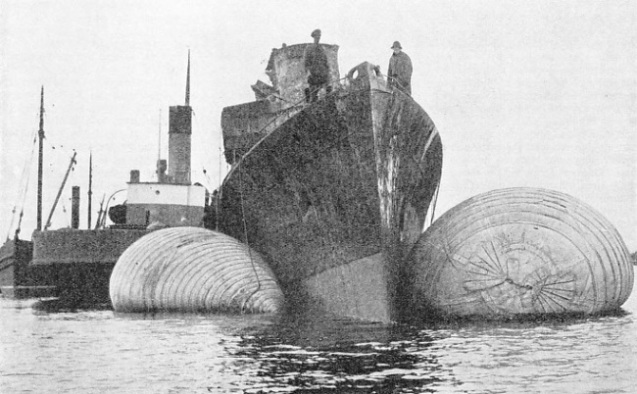

The value of scrap was understood immediately and any ship grounded or in shallow waters was laid bare by islanders. — Robertson ‘started the ball rolling’ by raising smaller destroyers, attaching large balloons called ‘Camels’.

But Ernest Cox’s purchase of the salvage rights for twenty-six destroyers and the two battleships, Seydlitz and the 26,180 ton Hindenburg, for £24,000 was the moment the industry was born. Cox a Wolverhampton businessman and knew nothing about the business of salvage although he had a very good knowledge of scrap metal.

And Robert McCrone, the first to not only be able to lift ships but to also do so profitably.

Both Cox and McCrone were helped by the knowledge of Tom McKenzie, a Glaswegian engineer and naval salvage expert.

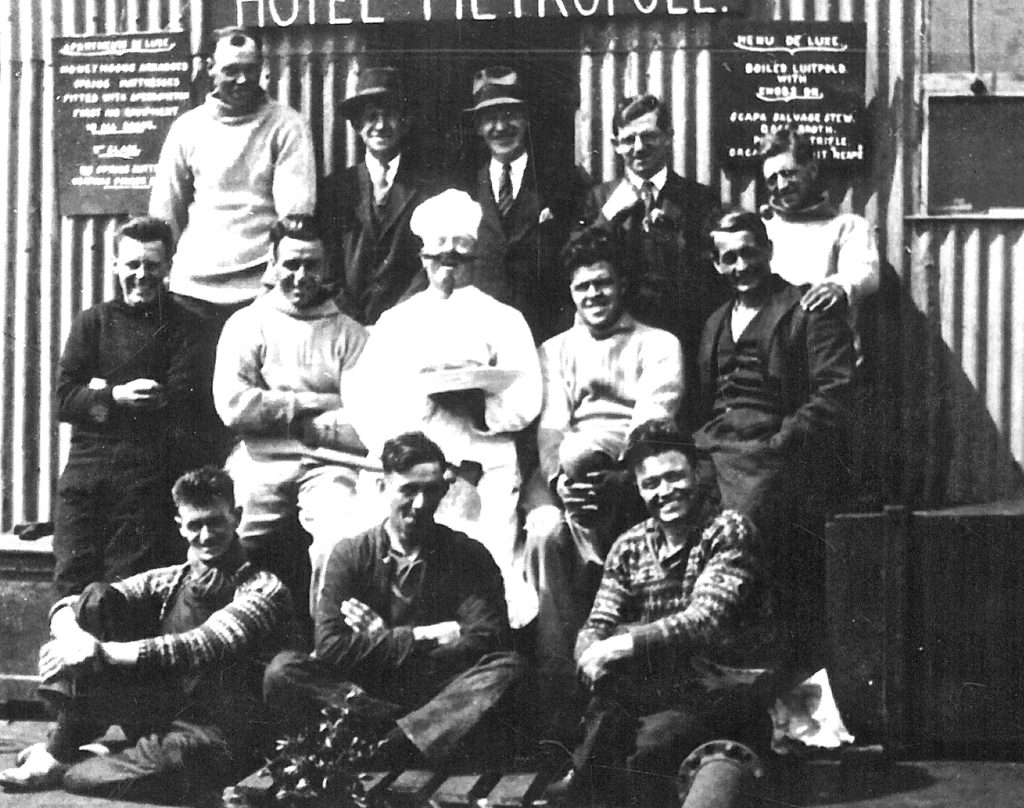

And the divers and teams of both Cox and Danks and later Metal Industries.

Divers worked in the dark and cold confined spaces wearing cumbersome and heavy helmets, weights and boots.

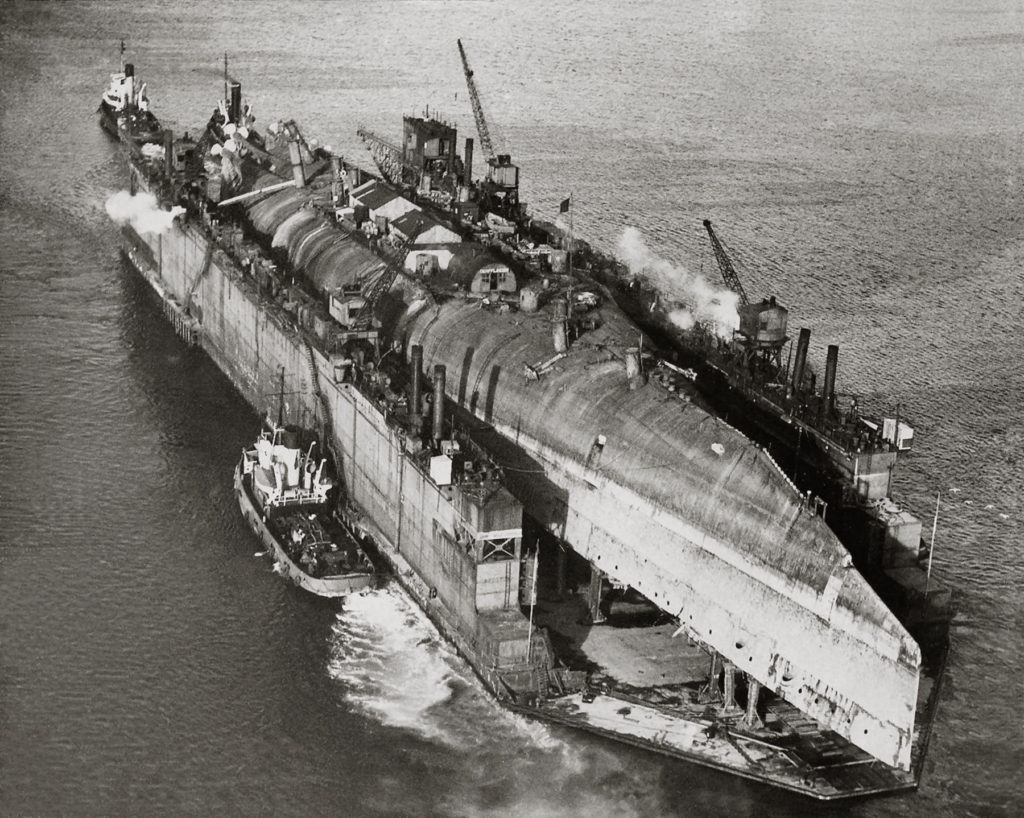

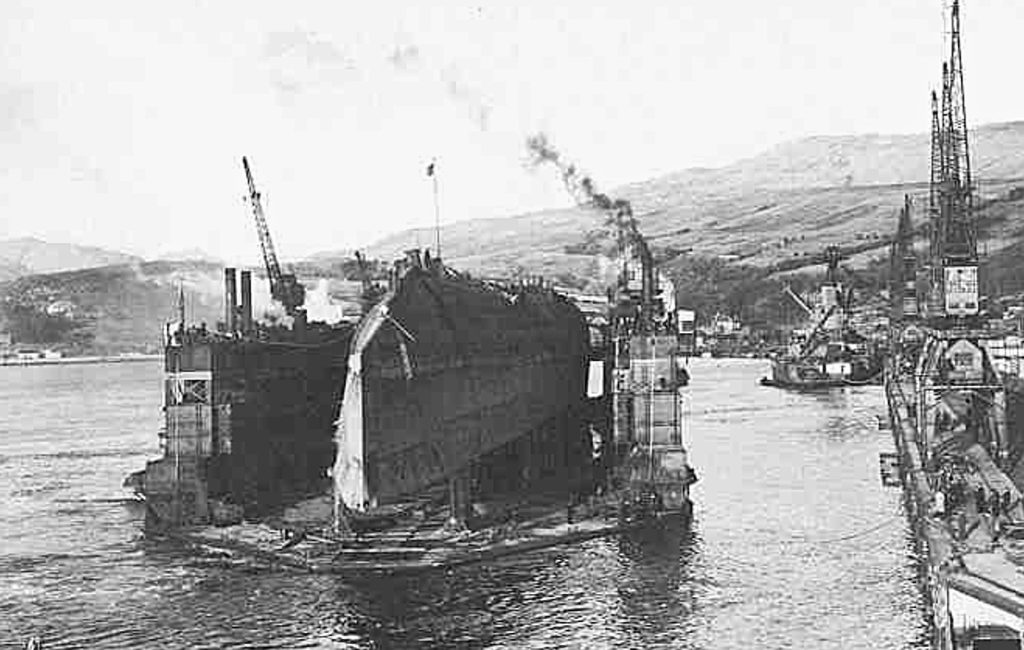

Using a specially converted German dry dock and rows of powerful winches, Cox used the ebb and flow of the tides to naturally lift ships before the final journey to Lyness to strip off much of the excess structure before they were towed south to Rosyth to scrapyards.

As the spring tidal difference was between ten to twelve foot, Cox’s men could take up the slack and then take their load into shallower waters where the entire process could be repeated.

The Hindenburg was the first huge challenge. Inside her hull conditions were appallingly tough. It was like a ‘vast submarine forest’, marine growth was everywhere. Divers worked in the dark feeling their way around until patches could be applied to the holes and the water pumped out. At one point she was raised, after £30,000 had been spent, only to sink again.

The next time, working on a battlecruiser, the Moltke, compressed air was pumped in at the same time water was pumped out. The hull was compartmentalised to that the list could be corrected by adjusting pressure as she went up. It was an exact, dangerous science.

Specially built towers, made from old cut-up boilers, provided the airlocks through which workers could enter the hulls.

Derfflinger was raised but before she could be scrapped, war broke out again. She spent the war, turned over on her back, lying next to an old Jutland rival and Jellicoe’s flagship at the battle, HMS Iron Duke, the ‘Iron Dog’ (‘der eisener Hund’) laying beside the ‘Tin Duck’.